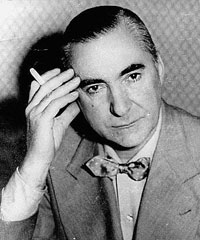

Curzio Malaparte

Curzio Malaparte (Italian pronunciation: [ˈkurtsjo malaˈparte]; born Kurt Erich Suckert; 9 June 1898 – 19 July 1957) was an Italian writer, filmmaker, war correspondent and diplomat. Malaparte is best known outside Italy due to his works Kaputt (1944) and The Skin (1949). The former is a semi-fictionalised account of the Eastern Front during the Second World War and the latter is an account focusing on morality in the immediate post-war period of Naples (it was placed on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum).

During the 1920s, Malaparte was one of the intellectuals who supported the rise of Italian fascism and Benito Mussolini, through the magazine 900. Despite this, Malaparte had a complex relationship with the National Fascist Party and was stripped of membership in 1933 for his independent streak. Arrested numerous times, he had Casa Malaparte created in Capri where he lived under house arrest. After the Second World War, he became a filmmaker and moved closer to both Togliatti's Italian Communist Party and the Catholic Church (though once a staunch atheist), reputedly becoming a member of both before his death.[1][2][3]

Biography

[edit]Background

[edit]Born Kurt Erich Suckert in Prato, Tuscany, Malaparte was a son of a German father, Erwin Suckert, a textile-manufacturing executive, and his Lombard wife,[4] née Evelina Perelli. He was educated at Collegio Cicognini in Prato and at La Sapienza University of Rome. In 1918 he started his career as a journalist. Malaparte fought in the First World War, earning a captaincy in the Fifth Alpine Regiment and several decorations for valor.

His chosen surname Malaparte, which he used from 1925 onward, means "evil/wrong side" and is a play on Napoleon's family name "Bonaparte" which means, in Italian, "good side".

National Fascist Party

[edit]In 1922, he took part in Benito Mussolini's March on Rome. In 1924, he founded the Roman periodical La Conquista dello Stato ("The Conquest of the State", a title that would inspire Ramiro Ledesma Ramos' La Conquista del Estado). As a member of the Partito Nazionale Fascista, he founded several periodicals and contributed essays and articles to others, as well as writing numerous books, starting from the early 1920s, and directing two metropolitan newspapers.

In 1926, he founded with Massimo Bontempelli the literary quarterly "900". He later became a co-editor of Fiera Letteraria (1928–31), and an editor of La Stampa in Turin. His polemical war novel-essay, Viva Caporetto! (1921), criticized corrupt Rome and the Italian upper classes as the real enemy (the book was forbidden because it offended the Royal Italian Army).

Coup d'État: The Technique of Revolution

[edit]In Coup d'État: The Technique of Revolution, first published in French in 1931 as Technique du coup d`Etat, Malaparte set out a study of the tactics of coup d'etat, particularly focusing on the Bolshevik Revolution and that of Italian fascism. Here he stated that "the problem of the conquest and defense of the State is not a political one ... it is a technical problem", a way of knowing when and how to occupy the vital state resources: the telephone exchanges, the water reserves and the electricity generators, etc. He taught a hard lesson that a revolution can wear itself out in strategy.[5] He emphasizes Leon Trotsky's role in organising the October Revolution technically, while Lenin was more interested in strategy. The book emphasizes that Joseph Stalin thoroughly comprehended the technical aspects employed by Trotsky and so was able to avert Left Opposition coup attempts better than Kerensky.

For Malaparte, Mussolini's revolutionary outlook was very much born of his time as a Marxist. On the topic of Adolf Hitler, the book was far more doubtful and critical. He considered Hitler to be a reactionary. In the same book, first published in French by Grasset, he entitled chapter VIII: A Woman: Hitler. This led to Malaparte being stripped of his National Fascist Party membership and sent to internal exile from 1933 to 1938 on the island of Lipari.

Arrests and Casa Malaparte

[edit]He was freed on the personal intervention of Mussolini's son-in-law and heir apparent Galeazzo Ciano. Mussolini's regime arrested Malaparte again in 1938, 1939, 1941, and 1943, imprisoning him in Rome's jail Regina Coeli. During that time (1938–41) he built a house with the architect Adalberto Libera, known as the Casa Malaparte, on Capo Massullo, on the Isle of Capri.[6] It was later used as a location in Jean-Luc Godard's film Le Mépris.

Shortly after his time in jail he published books of magical realist autobiographical short stories, which culminated in the stylistic prose of Donna come me (Woman Like Me, 1940).[7]

Second World War and Kaputt

[edit]His remarkable knowledge of Europe and its leaders is based upon his experience as a correspondent and in the Italian diplomatic service. In 1941 he was sent to cover the Eastern Front as a correspondent for Corriere della Sera. The articles he sent back from the Ukrainian Fronts, many of which were suppressed, were collected in 1943 and brought out under the title The Volga Rises in Europe. The experience provided the basis for his two most famous books, Kaputt (1944) and The Skin (1949).

Kaputt, his novelistic account of the war, surreptitiously written, presents the conflict from the point of view of those doomed to lose it. Malaparte's account is marked by lyrical observations, as when he encounters a detachment of Wehrmacht soldiers fleeing a Ukrainian battlefield,

When Germans become afraid, when that mysterious German fear begins to creep into their bones, they always arouse a special horror and pity. Their appearance is miserable, their cruelty sad, their courage silent and hopeless.

In the foreword to Kaputt, Malaparte describes in detail the convoluted process of writing. He had started writing it in the autumn of 1941, while staying in the home of Roman Souchena in the Ukrainian village of Pestchianka, located near the local "House of the Soviets" which was requisitioned by the SS; the village was then just two miles behind the front. Souchena was an educated peasant, whose small home library included the complete works of Pushkin and Gogol. Souchena's young wife, absorbed in Eugene Onegin after a hard day's work, reminded Malaparte of Elena and Alda, the two daughters of Benedetto Croce. The Souchena couple helped Malaparte's writing project, he keeping the manuscript well hidden in his house against German searches and she sewing it into the lining of Malaparte's clothing when he was expelled from the Ukrainian front because of the scandal of his articles in Corriere della Sera. He continued the writing in January and February 1942, which he spent in Nazi-occupied Poland and at the Smolensk Front. From there he went to Finland, where he spent two years - during which he completed all but the final chapter of the book. Having contracted a serious illness at the Petsamo Front in Lapland, he was granted a convalescence leave in Italy. En route, the Gestapo boarded his plane at the Tempelhof Airport in Berlin and the belongings of all passengers were thoroughly searched. Fortunately, no page of Kaputt was in his luggage. Before leaving Helsinki, he had taken the precaution of entrusting the manuscript to several Helsinki-based diplomats: Count Agustín de Foxá, Minister at the Spanish Legation; Prince Dina Cantemir, Secretary of the Romanian Legation; and Titu Michai, the Romanian press attaché. With the help of these diplomats, the manuscript finally reached Malaparte in Italy, where he was able to publish it.

One of the most well-known and often quoted episodes of Kaputt concerns the interview which Malaparte - as an Italian reporter, supposedly on the Axis side - had with Ante Pavelić, who headed the Croat puppet state set up by the Nazis.

While he spoke, I gazed at a wicker basket on the Poglavnik's desk. The lid was raised and the basket seemed to be filled with mussels, or shelled oysters, as they are occasionally displayed in the windows of Fortnum and Mason in Piccadilly in London. Casertano looked at me and winked, "Wouldn't you like a good oyster stew?"

"Are they Dalmatian oysters?" I asked the Poglavnik.

Ante Pavelic removed the lid from the basket and revealed the mussels, that slimy and jelly-like mass, and he said smiling, with that tired good-natured smile of his, "It is a present from my loyal Ustashis. Forty pounds of human eyes."

Milan Kundera's view of the Kaputt is summarized in his essay The Tragedy of Central Europe:[8]

It is strange, yes, but understandable: for this reportage is something other than reportage; it is a literary work whose aesthetic intention is so strong, so apparent, that the sensitive reader automatically excludes it from the context of accounts brought to bear by historians, journalists, political analysts, memoirists.[9]

According to D. Moore's editorial note, in The Skin,

Malaparte extends the great fresco of European society he began in Kaputt. There the scene was Eastern Europe, here it is Italy during the years from 1943 to 1945; instead of Germans, the invaders are the American armed forces. In all the literature that derives from the Second World War, there is no other book that so brilliantly or so woundingly presents triumphant American innocence against the background of the European experience of destruction and moral collapse.[10]

The book was condemned by the Roman Catholic Church, and placed on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum.[11] The Skin was adapted for the cinema in 1981.

From November 1943 to March 1946 he was attached to the American High Command in Italy as an Italian Liaison Officer. Articles by Curzio Malaparte have appeared in many literary periodicals of note in France, the United Kingdom, Italy and the United States .

Film directing and later life

[edit]

After the war, Malaparte's political sympathies veered to the left and he became a member of the Italian Communist Party.[12] In 1947, Malaparte settled in Paris and wrote dramas without much success. His play Du Côté de chez Proust was based on the life of Marcel Proust and Das Kapital was a portrait of Karl Marx. Cristo Proibito ("Forbidden Christ") was Malaparte's moderately successful film—which he wrote, directed and scored in 1950. It won the "City of Berlin" special prize at the 1st Berlin International Film Festival in 1951.[13] In the story, a war veteran returns to his village to avenge the death of his brother, shot by the Germans. It was released in the United States in 1953 as Strange Deception and voted among the five best foreign films by the National Board of Review. He also produced the variety show Sexophone and planned to cross the United States on bicycle.[14] Just before his death, Malaparte completed the treatment of another film, Il Compagno P.

After the establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949, Malaparte became interested in the Maoist version of Communism. Malaparte visited China in 1956 to commemorate the death of the Chinese essay and fiction writer, Lu Xun. He was moved and excited by what he saw, but his journey was cut short by illness, and he was flown back to Rome. Io in Russia e in Cina, his journal of the events, was published posthumously in 1958. He willed his house in Capri to the Chinese Writers Association as a study and residence center for Chinese writers. But at the time of his death in 1957 there were no diplomatic relations with the People's Republic, so the transfer could not take place, and the family succeeded in changing the will.[15]

Malaparte's final book, Maledetti toscani, his attack on middle and upper-class culture, appeared in 1956. In the collection of writings Mamma marcia, published posthumously in 1959, Malaparte writes about the youth of the post-Second World War era with homophobic tones, describing it as effeminate and tending to homosexuality and communism;[16] the same content is expressed in the chapters "The pink meat" and "Children of Adam" of The Skin.[17] He died in Rome from lung cancer[18] on 19 July 1957.

Cultural representations of Malaparte

[edit]Malaparte's colorful life has made him an object of fascination for writers. An American journalist, Percy Winner, wrote about their relationship during the fascist ventennio (twenty year period) and the Allied Occupation of Italy, in the lightly fictionalized novel, Dario (1947) (where the main character's last name is Duvolti, or a play on "two faces"). In 2016, the Italian authors Rita Monaldi and Francesco Sorti published Malaparte. Morte come me (lit. 'Death Like Me'). Set on Capri in 1939, it gives a fictionalized account of a mysterious death in which Malaparte was implicated.[19]

Main writings

[edit]- Viva Caporetto! (1921, A.K.A. La rivolta dei santi maledetti)

- Technique du coup d'etat (1931) translated as Coup d'État: The Technique of Revolution, E. P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1932

- Donna come me (1940) translated as Woman Like Me, Troubador Italian Studies, 2006 ISBN 1-905237-84-7

- The Volga Rises in Europe (1943) ISBN 1-84158-096-1

- Kaputt (1944) ISBN 0-8101-1341-4 translated as Kaputt. 1948. New York Review Books Classics, 2007

- La pelle (1949) ISBN 0-8101-1572-7 translated as The Skin by David Moore, New York Review Books Classics, 2013, ISBN 978-1-59017-622-1 (paperback)

- Du Côté de chez Proust (1951)

- Maledetti toscani (1956) translated as Those Cursed Tuscans, Ohio University Press, 1964

- The Kremlin Ball (1957) translated by Jenny McPhee, 2018 ISBN 978-1681372099

- Muss. Il grande imbecille (1999) ISBN 978-8879841771

- Benedetti italiani postumo (curato da Enrico Falqui) (1961), edito da Vallecchi Firenze (2005), presentazione di Giordano Bruno Guerri ISBN 88-8427-074-X

- The Bird that Swallowed its Cage: The Selected Writings of Curzio Malaparte adapted and translated by Walter Murch, 2013 ISBN 9781619022812

- Diary of a Foreigner in Paris, translated by Stephen Twilley (New York Review Books Classics, 2020)

Filmography

[edit]- The Forbidden Christ (1950)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Maurizio Serra, Malaparte: vite e leggende, Marsilio, 2012, estratto

- ^ Senza disperazione e nella pace di Dio, Il Tempo, 20 luglio 1957.

- ^ "Malaparte, Curzio". Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana.

- ^ Vegliani, Franco (1957). Malaparte. Milano-Venezia: Edizioni Daria Guarnati. p. 33. Retrieved 22 June 2015.

- ^ Political Writings, 1953–1993 by Maurice Blanchot, Fordham Univ Press, 2010, p. xii

- ^ Welge, Jobst, Die Casa Malaparte auf Capri in Malaparte Zwischen Erdbeben, Eichborn Verlag 2007

- ^ McCormick, Megan. "Architects' summer retreats". Architecture Today. Retrieved 8 September 2023.

- ^ Milan Kundera's essay 'The Tragedy of Central Europe' in La Lettre internationale 1983.

- ^ Impossible Country, Brian Hall, Random House, 2011

- ^ Casa Malaparte, Capri, Gianni Pettena, Le Lettere, 1999, p. 134

- ^ Casa Malaparte, Capri, Gianni Pettena, Le Lettere, 1999, p. 134

- ^ William Hope: Curzio Malaparte, Troubador Publishing Ltd, 2000, ISBN 9781899293223 p. 95

- ^ "1st Berlin International Film Festival: Prize Winners". berlinale.de. Archived from the original on 15 October 2013. Retrieved 20 December 2009.

- ^ Casa Malaparte by Marida Talamona.Princeton Architectural Press, 1992, p. 19

- ^ Calamandrei, Silvia (1 August 2021), "Curzio Malaparte e gli intellettuali italiani alla scoperta della nuova Cina negli anni '50 (Curzio Malaparte and the Italian intellectuals in the discovery of China in the 1950s", Un Convegno a Prato

- ^ Contarini, Silvia (10 August 2013). "L'italiano vero e l'omosessuale". Nazione Indiana (in Italian). Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ^ Dall'Orto, Giovanni (11 February 2005). "Pelle, La [1949]. Omosessuali = comunisti pedofili femmenelle". Cultura gay (in Italian). Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ^ Time – Milestones, Jul. 29, 1957

- ^ Scorranese, Roberta (5 July 2016). "Curzio Malaparte sotto accusa nel nuovo romanzo di Monaldi-Sorti". Corriere della Sera (in Italian). Retrieved 28 September 2024.

Sources

[edit]- Malaparte: A House Like Me by Michael McDonough, 1999, ISBN 0-609-60378-7

- The Appeal of Fascism: A Study of Intellectuals and Fascism 1919–1945 by Alastair Hamilton (London, 1971, ISBN 0-218-51426-3)

- Kaputt by Curzio Malaparte, E. P. Dutton and Comp., Inc., New York, 1946 (biographical note on the book cover)

- Curzio Malaparte The Skin, Northwestern University Press, Evanston, 1997 (D. Moore's editorial note on the back cover)

- Curzio Malaparte: The Narrative Contract Strained by William Hope, Troubador Publishing Ltd, 2000, ISBN 978-1-899293-22-3

- The Bird that swallowed its Cage selected works by Malaparte translated by Walter Murch, Counterpoint Press, Berkeley, 2012, ISBN 1-619-02061-0.

- European memories of the Second World War by Helmut Peitsch (editor) Berghahn Books, 1999 ISBN 978-1-57181-936-9 Chapter Changing Identities Through Memory: Malaparte's Self-figuratios in Kaputt by Charles Burdett, p. 110–119

- Malaparte Zwischen Erdbeben by Jobst Welge, Eichborn Verlag, Frankfurt-am-Main 2007 ISBN 3-8218-4582-1

- Benedetti italiani: Raccolta postuma, di scritti di Curzio Malaparte, curata da Enrico Falqui (1961). Ristampato da Vallecchi Editore Firenze, (2005) prefazione di Giordano Bruno Guerri, ISBN 88-8427-074-X

- Il Malaparte Illustrato di Giordano Bruno Guerri (Mondadori, 1998)

External links

[edit]- Works by or about Curzio Malaparte at the Internet Archive

- Petri Liukkonen. "Curzio Malaparte". Books and Writers.

- Francobolli Pratesi

- The Traitor by Curzio Malaparte

- Why everyone hates Malaparte

- New York Books Review Curzio Malaparte

- MALAPARTE portrait of an Italian surrealist

- Newspaper clippings about Curzio Malaparte in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- Curzio Malaparte

- 1898 births

- 1957 deaths

- People from Prato

- Capri, Campania

- Italian war correspondents

- Italian communists

- Italian Roman Catholics

- Italian diplomats

- Italian dramatists and playwrights

- Italian essayists

- Italian male essayists

- Italian expatriates in France

- Italian fascists

- Italian film directors

- Italian military personnel of World War I

- Italian people of German descent

- Italian prisoners and detainees

- Italian male short story writers

- Italian people of Lombard descent

- Italian male novelists

- Italian male dramatists and playwrights

- 20th-century Italian novelists

- 20th-century Italian male writers

- 20th-century Italian dramatists and playwrights

- 20th-century Italian short story writers

- 20th-century Italian essayists

- Italian magazine editors

- Italian newspaper editors

- Italian male journalists

- Italian male non-fiction writers

- La Stampa editors

- Writers from Campania